I’m willing to bet that a few of you have noticed that the name of my Substack is Screen to Page. It’s hard to miss despite my terrible graphic design. I swear, when I can afford it, I’ll hire someone to make a real logo and brand identity. But, I refuse to use AI so here we are.

Why did I name this project Screen to Page, you ask? Great question.

“From Page to Screen” is an old Hollywood term that refers to screenwriters who would adapt works of prose, mostly novels and short stories, into screenplays. Those screenplays then became movies. Ergo, page to screen.

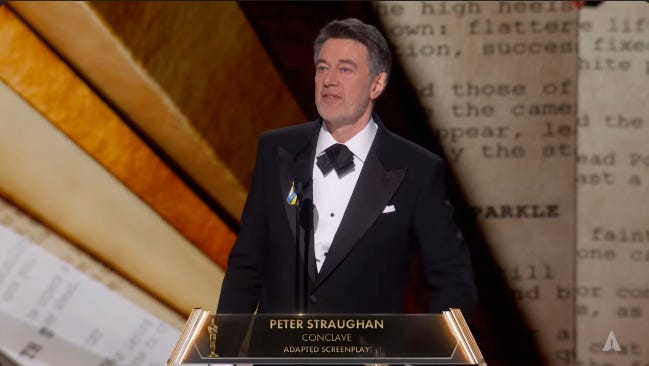

The Oscars were a few weeks ago and, if you’re reading this, I’m sure you saw that Conclave won Best Adapted Screenplay. That’s what we’re talking about here.

Richard Harris wrote a book about Cardinals – the ones who hide pedophiles not the cool red birds/baseball team – electing a new Pope. Some producers, likely Tessa Ross and Juliette Howell, read that book and were like “Catholics and Christians are a big demographic, I’m sure we could get someone to fund this as a film.” Then they hired Peter Straughan who was previously nominated for the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (adapted from the British television series of the same name), and boom, greenlit movie.

Intellectual Property plus Oscar Nominated Screenwriter plus Ralph Fiennes equals critical and box office success. The film made over $100 million on a $20 million budget. I’m sure there was more nuance to the development process than that, but that’s the gist of how things get made. This is a prime example of why Hollywood executives want I.P. to base their films on.

The only real difference between original screenplay and adapted screenplay is that the screenplays in the adapted category were novels, short stories, articles, or, occasionally, short films/television series before they were adapted for the screen.

The original impetus for my little project here was different. I have been writing original screenplays for more than a decade now. I’ve sold one. And it never got produced. This is, unfortunately, very normal. I don’t have an Oscar and Ralph Fiennes won’t take my calls. Yet.

I’ve worked in television development most of my career and 98% of sold projects never see the light of day beyond a Deadline article that no one even remembers. Here’s an article for one of my favorite projects I helped develop that never made it to air: Threesome.

I didn’t even get an article because my screenplay was bought by an independent producer rather than a studio. But, because it never got made, the rights reverted back to me.

When the 2023 writer’s strike happened, I found myself angry with the industry, out of work, and looking for a creative outlet that wouldn’t break the picket line. So, I took a screenplay I had already been paid for and decided to adapt that story into a novel.

My original plan was to publish each chapter on Substack as I wrote. Then something happened. I realized the manuscript was pretty damn good. So instead of sharing it here as I wrote, I decided to query literary managers and agents. I got three who were interested in the novel but ultimately chose not to represent it. Again, this is normal. I’m a first-time author. I’m a risk. So, just to make sure I wasn’t crazy, I submitted an early draft to the Launch Pad Prose Competition (R.I.P). My early draft landed in the top 50. Not too shabby for a work in progress.

What is the process for adapting a screenplay into a novel, when the adaptation process normally works in reverse? It was actually far easier than I expected it to be.

See a screenplay is really more of a blueprint regardless. It’s a document a director and production team use to guide them in telling a story visually. So, essentially, by having an already drafted screenplay I had an extremely detailed novel outline.

The next step was taking those scenes and expanding them. In screenwriting you’re not supposed to “direct on the page.” You don’t go in depth into character’s physical actions unless it’s pivotal to the scene. That’s blocking. The director will figure that out in rehearsal/on set. In a screenplay, you write in first person present tense and focus primarily on imagery and dialogue. You show the reader what the audience would see on screen.

Well written screenplays are more akin to poetry than novels. The job is to describe what is on screen in as few words as possible while still engaging your reader.

Novels are more complex. In a novel the story is told via character point of view. You not only have to direct on the page, but you also have to get inside your character’s heads in a way that cannot be done in a film or television series. Your reader needs to live in the mind of your point of view character. They need to empathize with that character. You have to show (not tell) how and why these characters act the way they do. All that work, in film, is done by the actor. In a novel, it’s all on the writer.

In a novel Brad Pitt isn’t going to help hide shitty character development by taking off his shirt.

I spent way too much time trying to figure out what point of view and tense I wanted to write in. I settled on third person omniscient, past tense. This allowed me to get into all of my character’s heads rather than just the leads. There are no small parts, people.

While this meant I had to do more work by fully dimensionalizing multiple characters, I welcomed it. I knew these characters in and out because of all the work I did when writing the screenplay, getting into their point of view was easy, and shifting between those points of views allowed me to turn a somewhat raunchy rom-com into a layered and nuanced story about love, family, and reconciliation. Something that was not possible within the confines of screenwriting. I can assure you the book is better than the screenplay.

After the editor gets their crack at it I’ll share more on when you can expect to see it.

So, since I reversed the typical process of adaptation I called this little project – and now my publishing company, cause I needed one when I bought the ISBN’s for my book – Screen to Page. Something that was meant for the screen but worked better on the page.

Life’s about adaptation. I’m adapting to the reality of the film and television industry by adapting my screenplay into a novel. If I’m being honest, writing this novel has reminded me how fun writing can be. So no matter how it turns out, that’s a win.